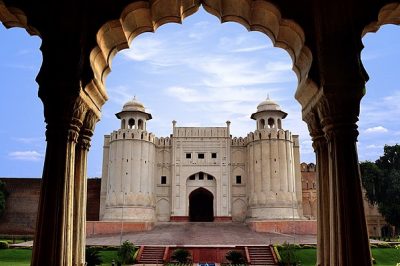

The Lahore Fort, also known as Shahi Qila, is a citadel in the city of Lahore, Punjab, Pakistan. The fort is located at the northern end of the Walled city of Lahore and spreads over an area greater than 20 hectares (49 acres). The fort symbolizes the power and splendor of the Mughal era with its imposing walls, intricate architecture, and rich history. It serves as a reminder of the cultural heritage and legacy that continues to resonate through the corridors of time.

Built during the reign of Emperor Akbar in the 16th century, the Lahore Fort has stood witness to centuries of history, witnessing the rise and fall of empires, the ebb and flow of cultures, and the changing tides of time. It served as the seat of power for many Mughal emperors, including Jahangir, Shah Jahan, and Aurangzeb, each leaving their mark on its magnificent architecture.

The Lahore Fort has witnessed centuries of conquests, political upheavals, and cultural shifts, making it a living chronicle of South Asian history. It has seen the rise and fall of empires, from the Mughals to the Sikhs and the British, each leaving their mark on its storied walls.

Adjacent to the Lahore Fort lies the Badshahi Mosque, another masterpiece of Mughal architecture and one of the largest mosques in the world.

One cannot help but marvel at the detailed craftsmanship displayed in every nook and cranny of the fort. From the delicate motifs adorning its walls to the grandeur of its palaces and halls, every inch of the Lahore Fort speaks volumes about the opulence and sophistication of Mughal craftsmanship.

The fort is divided into two sections: the administrative section, which is well connected with main entrances and includes gardens and Diwan-e-Khas for royal audiences. The second, a private and concealed residential section, is divided into courts in the north and accessible through the elephant gate.

It contains 21 notable monuments. It also contains Sheesh Mahal, spacious bedrooms, and small gardens. The exterior walls are decorated with blue Persian Kashi tiles. The original entrance faces the Maryam Zamani Mosque, and the enormous Alamgiri gate opens towards Hazuri Bagh through the majestic Badshahi mosque. The influence of Hindu architecture is seen in the zoomorphic corbels.

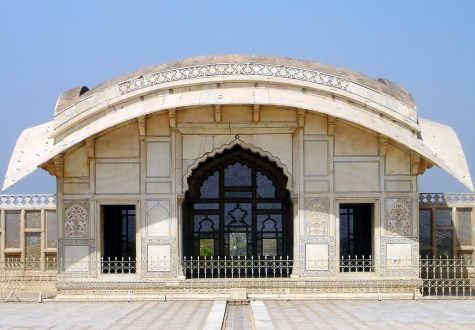

Naulakha Pavilion

The Naulakha Pavilion is an iconic sight of the Lahore Fort, built in 1633 during the Shah Jahan period. It is made of prominent white marble and is known for its distinctive curvilinear roof. It cost around 900,000 rupees, an excessive amount at that time. The structure derives its name from the Urdu word for 900,000, Naulakha.

The Naulakha Pavilion served as a personal chamber and was located west of the Sheesh Mahal, in the northern section of the fort. The pavilion inspired Rudyard Kipling, who named his Vermont home Naulakha in honor of the pavilion.

It reflects a mixture of contemporary traditions at the time of its construction, with a sloping roof based on a Bengali style and a baldachin from Europe, which makes evident the imperial and religious function of the pavilion. The marble shades of the pavilion are capped with merlons to hide the view from the grounds.

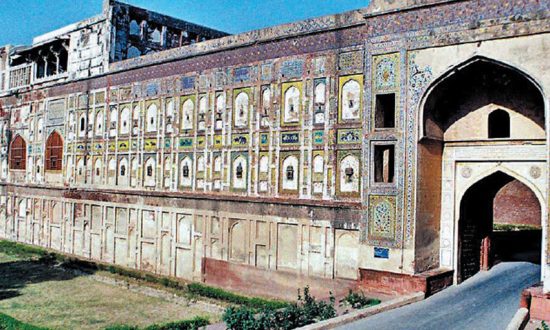

Emperor Jahangir ordered the construction of the massive “Picture Wall,” which is considered the most remarkable artistic triumph of the Lahore Fort. Unlike the Red Fort and Agra Fort, Lahore Fort’s ramparts were made of brick rather than red stone. The monumental Picture Wall is a large section of the outer wall exquisitely decorated with a vibrant array of glazed tile, faience mosaics, and frescoes.

Read More: Pakistan Embassy hosts Cambodian Delegation for collaboration

Picture Wall

The Picture Wall of Lahore Fort is a stunning example of the Mughal Empire’s creative prowess and cultural richness. Stretching over the northern and western walls of the fort, this magnificent structure spans approximately 1,450 feet in length and rises proudly to a height of 50 feet. Within its expanse lie 116 panels, each a masterpiece in its own right, showcasing various subjects ranging from elephant fights to celestial beings and polo games.

What makes the Picture Wall truly remarkable is its sheer size and the intricate detail and craftsmanship evident in every panel. Each scene is rendered meticulously, capturing moments of drama, beauty, and intrigue with breathtaking precision. As one walks along the length of the wall, it is as if stepping into a gallery of wonders, where each panel tells its unique story, inviting viewers to marvel at the richness of Mughal artistry.

Despite a cohesive narrative, the Picture Wall serves as a window into the vibrant world of Mughal culture and society. Scenes of elephant fights speak to the martial prowess of the empire, while depictions of angels and celestial beings hint at the spiritual beliefs and cosmological outlook of the time. And amidst it all, the timeless sport of polo, beloved by Mughal emperors and nobles, takes center stage, immortalized in vibrant hues and dynamic compositions.

The origins of the Picture Wall can be traced back to the reign of Emperor Jahangir, who initiated its construction. However, under the patronage of his son, Emperor Shah Jahan, the wall was brought to fruition, with decoration continuing well into the 1620s.

The Picture Wall was severely neglected and suffered from disrepair and damage. Conservation works at the site began in 2015 by the Aga Khan Trust for Culture and Walled City of Lahore Authority, which restored other Lahore landmarks such as the Wazir Khan Mosque and Shahi Hammam. Detailed wall documentation using a 3D scanner was completed in July 2016, after which conservation work started.

Beyond its historical significance, the Lahore Fort is also a symbol of resilience and cultural identity. Despite the passage of time and the ravages of wars and natural disasters, it has stood firm, an emblem of pride for the people of Lahore and Pakistan.

Preserving and protecting the Lahore Fort is a matter of historical conservation and a duty to future generations. As custodians of this priceless heritage, we must ensure that it continues to inspire awe and wonder for centuries to come.